Beyond 2025: The Challenge of Sustaining Sri Lanka’s Fiscal Overperformance

Between Sustained Revenue Growth & Recovery in Capex

Sri Lanka’s fiscal performance has shown notable improvement in recent years, driven largely by strict fiscal consolidation measures and reforms mandated under the IMF program. Historically, the country’s weak fiscal position was the result of inadequate revenue collection rather than excessive expenditure. Misallocation and improper prioritization of expenditure was also a cause in revenue mismanagement in Sri Lanka. The economic crisis made it clear to policymakers, academics, and the public that sound fiscal management is critical, as it directly influences debt repayment, interest rates, and inflation, essentially feeding into all aspects of the country’s economy.

Now the question lies with how Sri Lanka will manage its fiscal position beyond 2025. Compared to 2024, the country needed to raise an additional LKR 734 billion in tax revenue in 2025 to meet the IMF’s tax revenue target. More than half of this increase; about LKR 450 billion, was expected to come from vehicle import taxes. By September 2025, the Ministry of Finance reported that revenue from motor vehicles had reached LKR 429 billion.[i] This shows that by the end of this year the given target will be overachieved and as a result of it our tax revenue will also be higher than our estimates. While pent-up demand for vehicle imports may allow the 2025 revenue target to be met, the challenge lies in sustaining such gains over the medium to long term.

Shifting Tax Composition: From Income Tax to VAT Dominance

Looking ahead, the IMF program sets clear fiscal anchors: tax revenue must reach at least 14% of GDP (with overall revenue above 15% of GDP), primary expenditure must remain capped at 13% of GDP, and the government must maintain a primary surplus of 2.3%. These targets highlight two important shifts in Sri Lanka’s fiscal landscape. First, the country’s tax composition has changed significantly. With the VAT rates raised to 18% and most exemptions removed, VAT has now overtaken income tax as the largest single source of revenue.

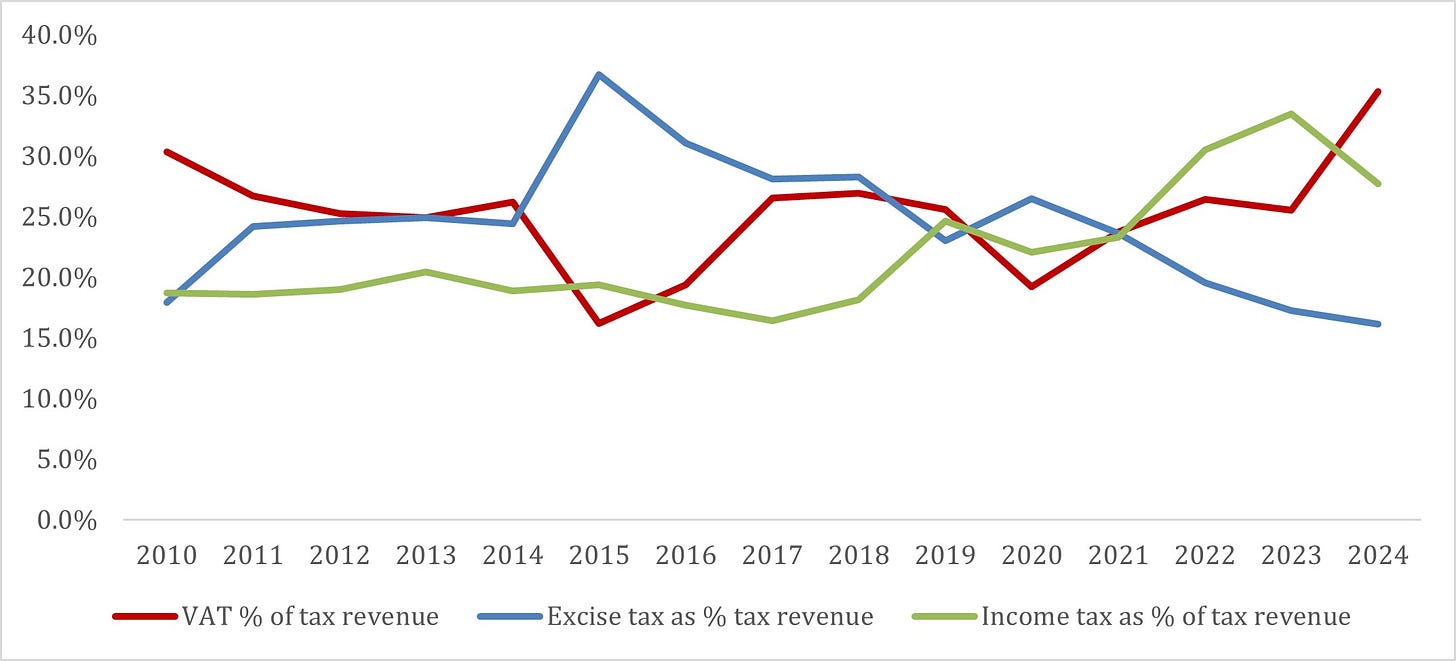

Contribution of VAT, Excise and Income taxes to tax revenue (2010-2024)

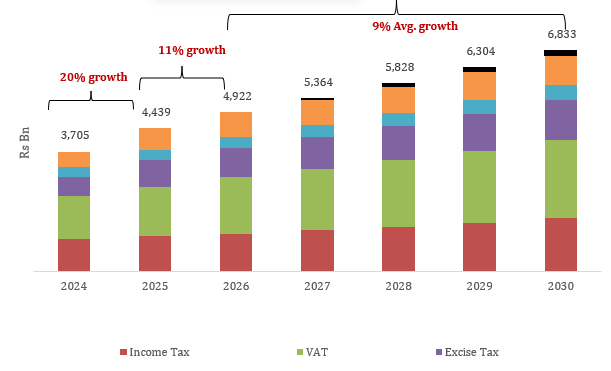

Within the last 10 years, Sri Lanka’s single main source of revenue has changed between Excise, Income taxes and VAT. This also represent the unsustainable tax policies introduced by the government under different regimes. Current revenue generating patterns and IMF projections suggest VAT will remain the dominant contributor in the coming years. Second, moving from 2025 to 2026, tax revenue is expected to grow by at least 11% YoY, equivalent to about LKR 500 billion. Meeting this target will require careful planning, as reliance on vehicle imports as the main driver would not be sustainable.

The IMF’s decision to set fiscal targets as a percentage of GDP rather than fixed nominal amounts has both benefits and risks for Sri Lanka. On the positive side, it provides flexibility, as targets automatically scale with the size of the economy. When growth picks up, nominal GDP expands and so does the tax revenue base, making percentage targets more realistic compared to rigid rupee amounts. It also insulates performance criteria from short-term shocks, since revenues like VAT and excise naturally rise with inflation and higher prices. However, this can also create a false sense of progress, as inflation-driven nominal gains may hide the lack of genuine tax base expansion. For Sri Lanka, the challenge is clear: in the short term, percentage-based targets are achievable with VAT hikes, pent-up import demand, and inflationary effects boosting collections. But over the medium term, with growth expected to average only 3.0–3.5% according to IMF projections, meeting and maintaining sustained revenue increases will depend less on cyclical or price effects and more on structural reforms.

Tax Revenue Projection (2025-2030)

Primary Surplus Over performance: Driven by Revenue and Capex Cuts

Over the past two years, Sri Lanka has consistently over performed in achieving a primary surplus. In 2024, the IMF set a quantitative performance target of LKR 300 billion, but the actual primary surplus reached LKR 650 billion. Similarly, in 2025, the target was approximately LKR 734 billion, yet by July the surplus had already climbed to LKR 974 billion. This over performance has been driven by two main factors: stronger-than-expected revenue collections and significantly lower capital expenditure.

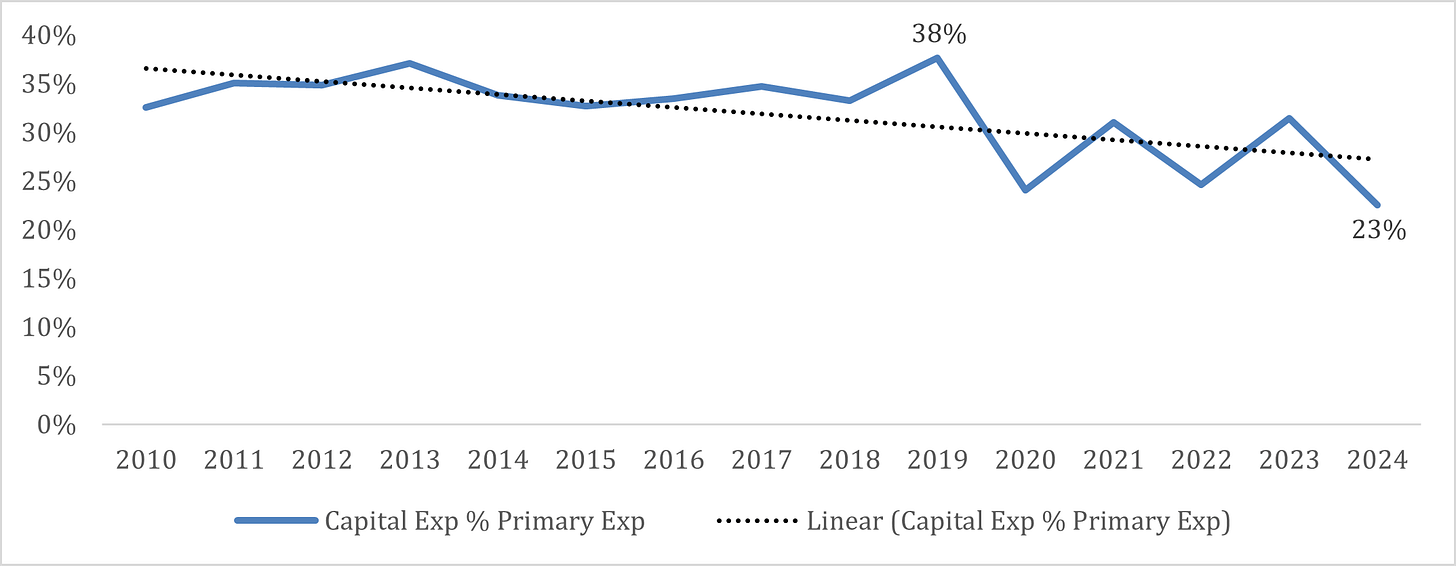

A closer look at capital expenditure trends over the last decade highlights a sharp contraction in recent years. While budget allocations for capital expenditure have often exceeded LKR 1 trillion, actual utilization has been far lower. For instance, in 2024, the budget allocated LKR 1.2 trillion for capital expenditure, but only LKR 817 billion was actually spent. The underspending of capital expenditure is primarily driven by the stringent procedures and bureaucratic red tape surrounding government spending, rather than by officials’ reluctance to utilize the funds. This issue was also highlighted by the International Monetary Fund in its most recent review.

Capital Expenditure as a % of Primary Expenditure

This underutilization has contributed to the Treasury building a sizable cash buffer, now estimated at over LKR 1 trillion. The existence of this buffer has provided valuable flexibility for the Treasury in managing its borrowing costs more effectively. This also provide space for the government to pay down its domestic debt, which we have seen the treasury doing in the past couple of months, especially with short end government securities.

However, this strategy has also altered the structure of Sri Lanka’s economy. While reduced capital expenditure and strong fiscal buffers offer short- to medium-term stability in debt management, the long-term trade-off is weaker investment in infrastructure and growth-enhancing projects. Over time, this underinvestment risks constraining productivity, private sector competitiveness, and overall growth potential. In other words, fiscal over performance achieved through spending compression may stabilize the present but could undermine the foundation for future growth. Sri Lanka’s challenge, therefore, is to balance short-term fiscal prudence with the longer-term need to invest in development.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the opinions of any organization the author is currently or previously affiliated with. The author assumes full responsibility for any errors or omissions.

[i] https://www.themorning.lk/articles/wOD5sWCXGSd3tDkEqLOJ