Sri Lanka's $50bn plus External Debt burden - what's public & what's private sector

Explaining the $50 billion odd number that pops up

Quite a few articles refer to a $50 billion odd number as Sri Lanka’s external debt burden. And that number is clearly different from the public external debt burden I described in the previous article, because the total external debt includes other foreign liabilities, especially those of the financial sector and private sector firms. And not all of this $50 billion plus debt falls under the sovereign default and debt restructuring.

CBSL releases the external debt data on a quarterly basis - the latest being up to end-Sept 2022 - based on the World Bank-IMF Quarterly External Debt Statistics reporting standards. This reporting follows the residency based definition to identify what is external (or foreign) debt - that is debt held by non-residents regardless of legal jurisdiction and currency denomination.

In case that last sentence does not make sense, give my previous article a read first:

Market value vs. Face value

The curious case about this quarterly CBSL dataset on total external debt is that market traded debt securities - like International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs) - are reported using their market value rather than their nominal face value (outstanding value of the debt that needs to be repaid). When the bonds were trading at market values close their face value, until 2019, this is not an issue. Since 2020 the market values dropped amidst concerns about default, so the total outstanding under market value became significantly lower than under face value. By Sept 2022, this deviation was a massive $8.1 billion! Therefore, it is vital to adjust the data manually to calculate face value outstanding, for which the data is provided in the CBSLs excel.

Figure 1: Market value vs. Face value of International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs) held by non-residents, US$ million

This adjustment applies for a few other instruments besides the government’s ISBs - rupee Treasury bonds/bills held by foreigners (listed under govt) and the Sri Lankan Airlines eurobond (listed under Other Sectors, which includes SOEs). As a result the total deviation between market and face value is about $8.1 billion (but $8.0 billion of the deviation comes from the foreign held ISBs alone).

Table 1: Market value vs. Face value of overall external debt, US$ billion

Therefore, the overall external debt burden is about $56 billion over the most recent quarters as shown by the face value figure above. Of this, a significant portion is listed under sectors outside the central government.

Table 2: Face value of external debt outside of central govt, US$ billion

What’s all that debt under the Central Bank?

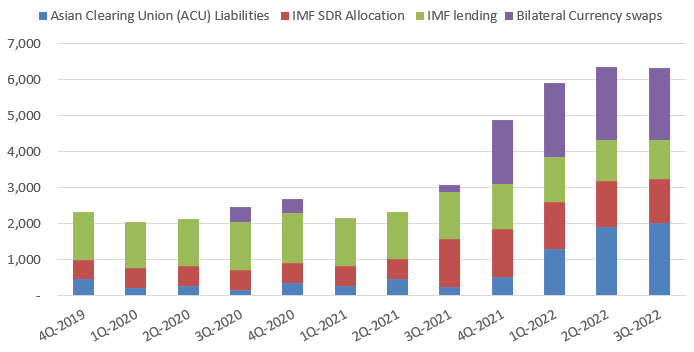

In my previous article, there was only $3.2 billion in external debt listed under CBSL, but here there’s $6.4 billion. That’s because in addition to the IMF loans and bilateral currency swaps covered under public debt, CBSL also has two other additional liabilities - the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) allocation and the Asian Clearing Union (ACU) trade liabilities.

The SDR allocation of about $1.2 billion is provided proportionally to all IMF members - the most recent and largest allocation happened in Aug 2021 - and need not be repaid, its simply an accounting entry.

The ACU liabilities are a regular feature that allows regional countries (South Asia, Iran & Myanmar) to save up on dollar reserves in settling trade payments on a netting out basis every 2 months. Usually ACU liabilities of CBSL are about $200-500 million. But since early 2022, the ACU members have been considerate enough to allow Sri Lanka to essentially borrow up to $2 billion in ACU trade liabilities - so we’ve imported from our neighbors (mostly India) without paying. As CBSL builds up its forex reserves, it will have to gradually pay it down.

Figure 2: CBSL’s external debt, US$ million

How is the rest of the financial sector borrowing abroad?

The quarterly data shows that the deposit taking institutions (banks & finance companies) have been reducing their short-term loans, to be replaced by a rise in currency and deposits from non-residents since mid-2021. This coincided with the worsening in Sri Lanka’s forex availability situation and market access.

A possibility is that non-residents have been building up rupee deposits in domestic banks as its been difficult to make outward payments. Some non-resident Sri Lankans also facilitate forex payments abroad in return for rupee deposits domestically. USD fixed deposit interest rates are also high at local banks (6% and above).

Figure 3: Deposit taking financial institutions’ external debt, US$ million

What about the rest of the sectors?

The template oddly reports private sector and SOE debt together under Other Sectors. But luckily there is some breakdown.

As at Sept 2022, the biggest liability here is intercompany loans of FDI firms registered with the Board of Investment (BOI) amounting to $5.6 billion. Private sector firms have $2.3 billion and SOEs have $1.4 billion in foreign loans according to this data. With a further $175 million in the Sri Lankan Airlines (an SOE) eurobond, that is currently in default. There is also $1.3 billion in trade credit - most of which is likely for petroleum and coal imports by CPC and CEB (the two large energy SOEs).

Figure 4: Private sector & SOEs external debt, US$ million

Takeaways

Use the face value to give a better picture of Sri Lanka’s external debt burden, which was around $56 billion at Sept 2022. The $48 billion market value figure is also accurate, but for that definition. So, being aware of these complexities is vital when reporting/discussing debt.

The government is not the only entity with external debt, the central bank, financial institutions, SOEs and private sector firms also do. Keeping track of how these other borrowers’ external liabilities change is also vital.

The external debt that is in sovereign default and are to be restructured are debt that is under the central government and the SOEs, as I explained about previously. It does not apply to the entire $56 billion external debt, especially the debt reported under the financial sector and private sector.

As discussed in my previous article, there is also the government’s domestic foreign currency debt to be aware of, which do not fall within this $56 billion. The $1.75 billion in ISBs held by domestic banks, the SLDBs and other domestic dollar debt of the government and the dollar loans of SOEs from domestic banks need to be factored in too.

Note that the external debt numbers for the government in the quarterly CBSL external debt statistics seem to have slight differences to what’s reported by Ministry of Finance, which I explained in the previous article. There could be private sector, financial sector or SOE external debts not covered by this CBSL data reporting. There will always be things missed, misreported or overlooked. Data reporting improves over time. Just glad to have at least this quarterly data set going back to 2013 to work with.